George Rogers Clark issue of 1929 (Scott #651)

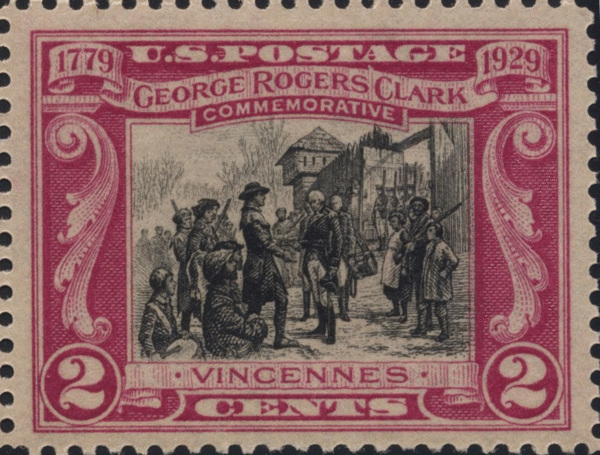

Please allow me to introduce you to my favorite U.S. stamp:

Single George Rogers Clark stamp

Isn't that drool-worthy? It is printed by a type of recess printing known as intaglio. A master artist takes weeks — sometimes months — with a scribing tool on a piece of copper. There is no room for error. He works in mirror-image. Everywhere he scratches, ink will be deposited. Every place left unscratched, the color of the paper will show through.

In this style of stamp, which is called frame and vignette, the artist cuts two plates: in this case, the one that takes the scarlet ink, and the one that takes the black ink.

How it works is this: the frame plate is inked all over with a wool (or these days, synthetic) roller. The ink gets both into the crevices and onto the smooth copper. Then, a sharp blade, called a doctor blade, squeegees the surface of the plate. The flat areas are now devoid of ink, but the ink remains in the crevices. High-quality paper is dampened, then pressed under enormous pressure against the engraving plate by another plate or roller. The paper is squeezed into the crevices, where it picks up the ink. It is allowed to dry, and then the same process is repeated with the vignette, or image inside the frame.

The plates are expensive to produce; they wear out, so there have to be duplicates (don't worry, the engraving usually only happens once and is mechanically repeated); they have to be replaced once they wear out — there are lots of costs. Coupled with the tiny number of people skillful enough to do this, and the salaries they can command, intaglio is an extremely expensive way to make stamps, and is rarely used these days.

You can always tell an intaglio stamp, by (carefully!) dragging the back edge of a fingernail across the stamp. Every tiny line will register as a bump. It's exquisite. It's art on a tiny canvas.

This stamp — an oversized issue for the day (about 40mm × 31mm) and a rarity to be printed in two colors — is amazing. Why this topic, George Rogers Clark's capture of a British fort 150 years prior, was chosen for this honor, and not, say, the sesquicentennial of the signing of the Declaration of Independence three years prior, baffles me. But they did it.

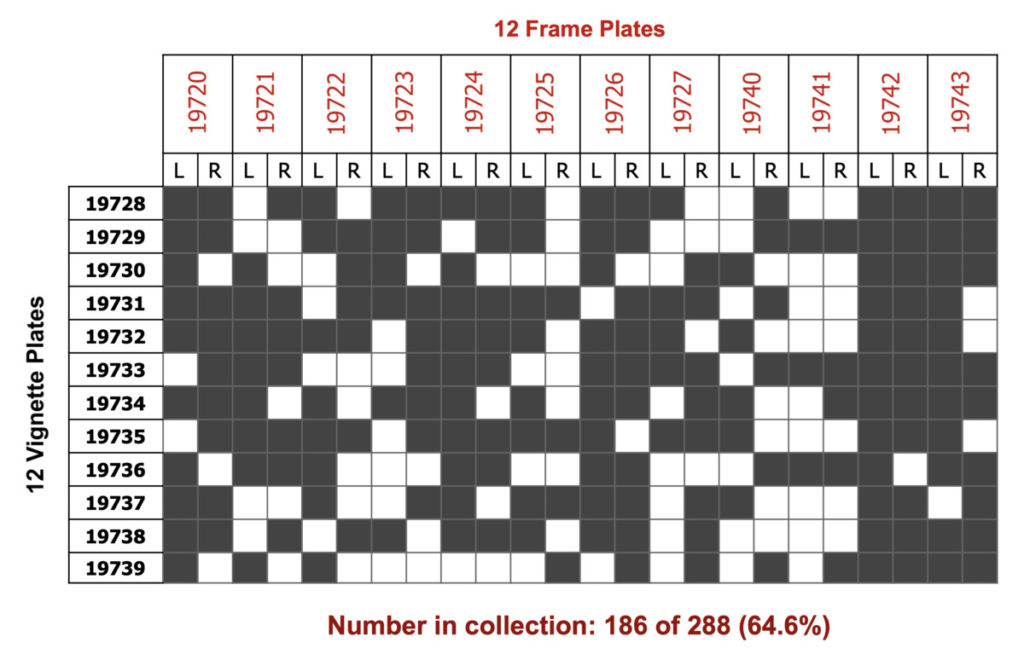

The beauty is not the only reason it's my favorite stamp, however: there's also some cool math stuff. As was the custom, when this stamp was being produced, each plate was numbered. The numbers are printed by the plates in the waste paper around the block of stamps, or selvedge. Twelve frame plates were engraved, twelve vignette plates were engraved, and all 144 combinations exist.

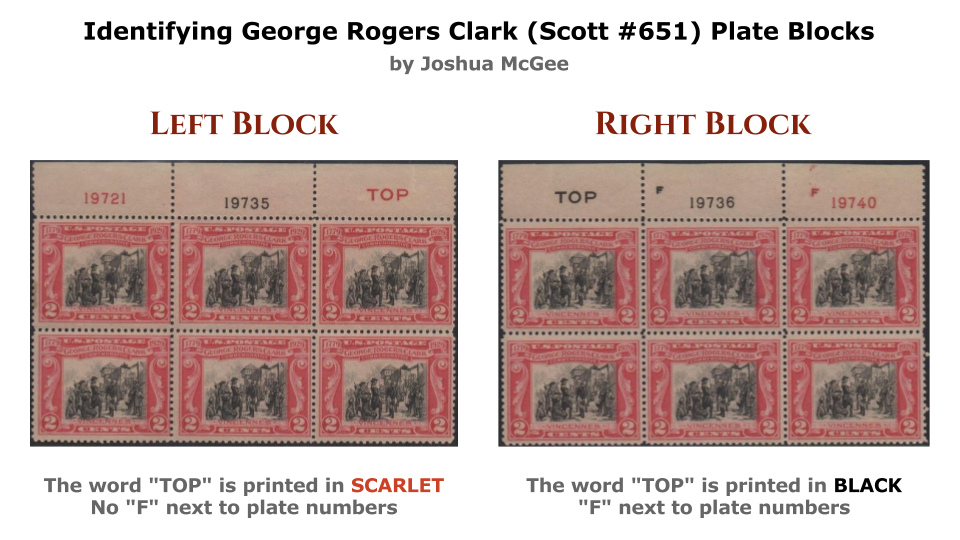

More interestingly, they are all approximately the same rarity. To spice things up even more, there are plate blocks from the left and right of the sheet, which was cut into two panes for sale. The left side has the word "Top" on the selvedge above one stamp in scarlet, then the plate numbers (in their appropriate colors; they are after all deposited by the plate) above two more stamps. They are collected in 3×2 blocks. On the right side, the word "Top" is in black above one of the steps, and the order of the plate numbers is reversed, and the letter "F" appears next to each plate. So all told, there are 288 collectible plate blocks, all of which exist, all of which are obtainable, and all of which are pretty cheap (a whole collection would cost about $3000 — and a lot of time searching through boxes!)

If you've wondered how someone can devote a lifetime of study to one single stamp, here is an example. Once all the plates and positions are obtained, the collector could start studying freaks, or plate flaws, or different plate states. The collector could obtain trial proofs, india paper proofs, and printer's waste. The collector could probably win a major award at an exhibition with a study of this one stamp.

I collect plate blocks of this issue. Here is my checklist at the moment:

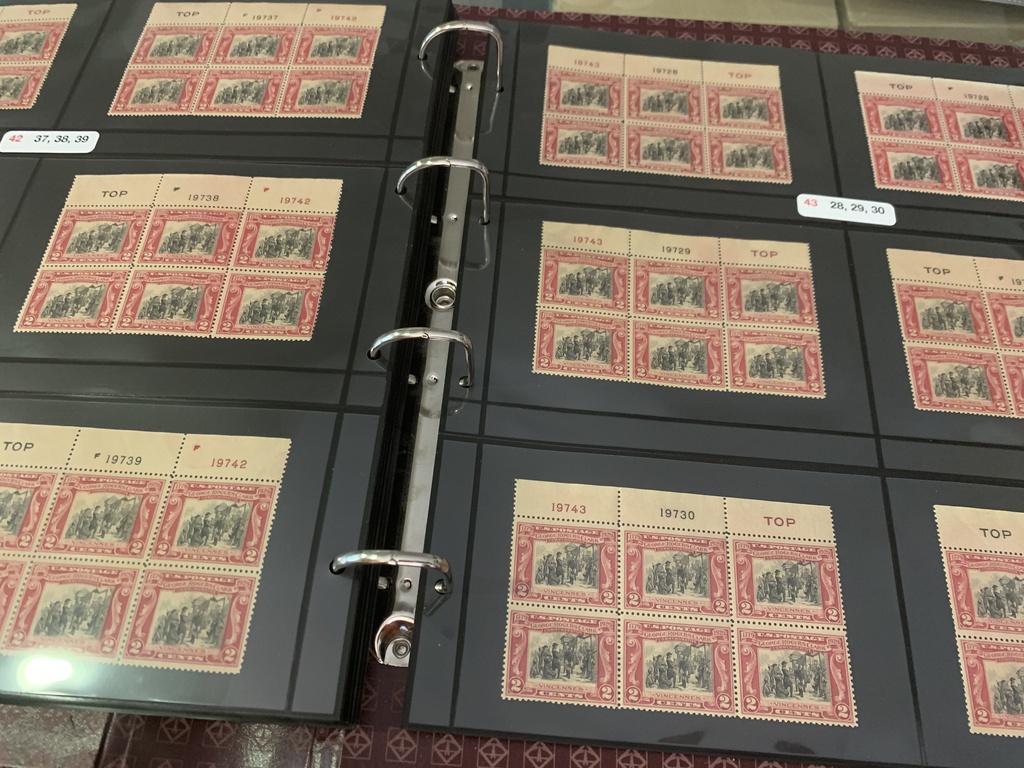

I have a whole album, with a slipcase, devoted to this one issue.

George Rogers Clark album pages

As you can see, I have a way to go. Wish me luck!